Fifty years ago in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, the murderous Khmer Rouge regime inaugurated its ghastly reign, turning the entire country into a gigantic prison camp – literally overnight.

Despite having been dragged unwillingly into America’s war next door, Cambodia’s citizens – from the peasant farmers who made up 80% of the population to the educated middle class in the cosmopolitan capital city – universally desired political independence and neutrality. So, when the black-pajama-clad teenagers rolled into Phnom Penh carrying AK-47s and rocket launchers, joyfully shouting that the war was over, and American puppet General Lon Nol had been deposed, many city-dwellers joined in the celebration.

Any initial excitement was quickly extinguished by the shocking reality of what life under these new homegrown “liberators” might look like. The Khmer Rouge cadres ordered the entire population of Phnom Penh – more than 2 million men, women and children – to evacuate the city and head into the countryside. They claimed that the Americans planned to carpet bomb the city, an audacious lie that was believable only because the U.S. had been bombing the Cambodian countryside for years, killing more than 100,000 civilian non-combatants in its effort to disrupt the so-called Ho Chi Minh trail.

When a father objected to the immediate displacement, pointing out that his daughter was attending a class or event on the other side of the city, he was shot point blank on the steps of his home. When a doctor angrily refused to leave a patient mid-surgery, the doctor and patient were executed on the spot.

And so it began.

And for the next three years, 8 months and 21 days, this gentle tropical jewel of a nation was a living hell, a nightmare from which none could wake. By the time the neighboring Vietnamese intervened and deposed the Khmer Rouge, nearly a quarter of Cambodia’s nine million residents had been executed, or had died of preventable starvation. Hundreds of thousands who had fled the country were living in refugee camps in nearby Thailand. Many of those would not be able to return home for nearly almost two decades.

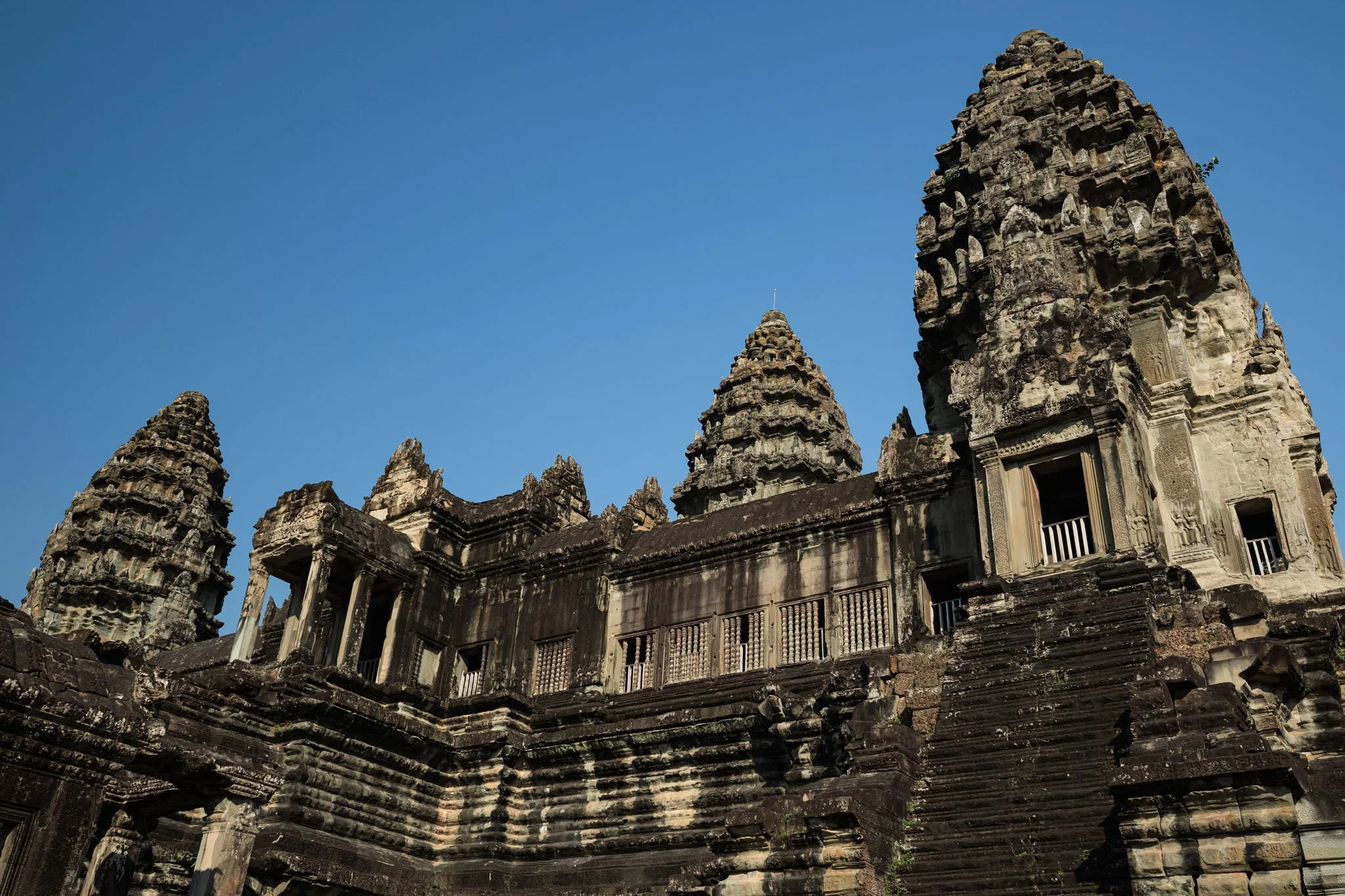

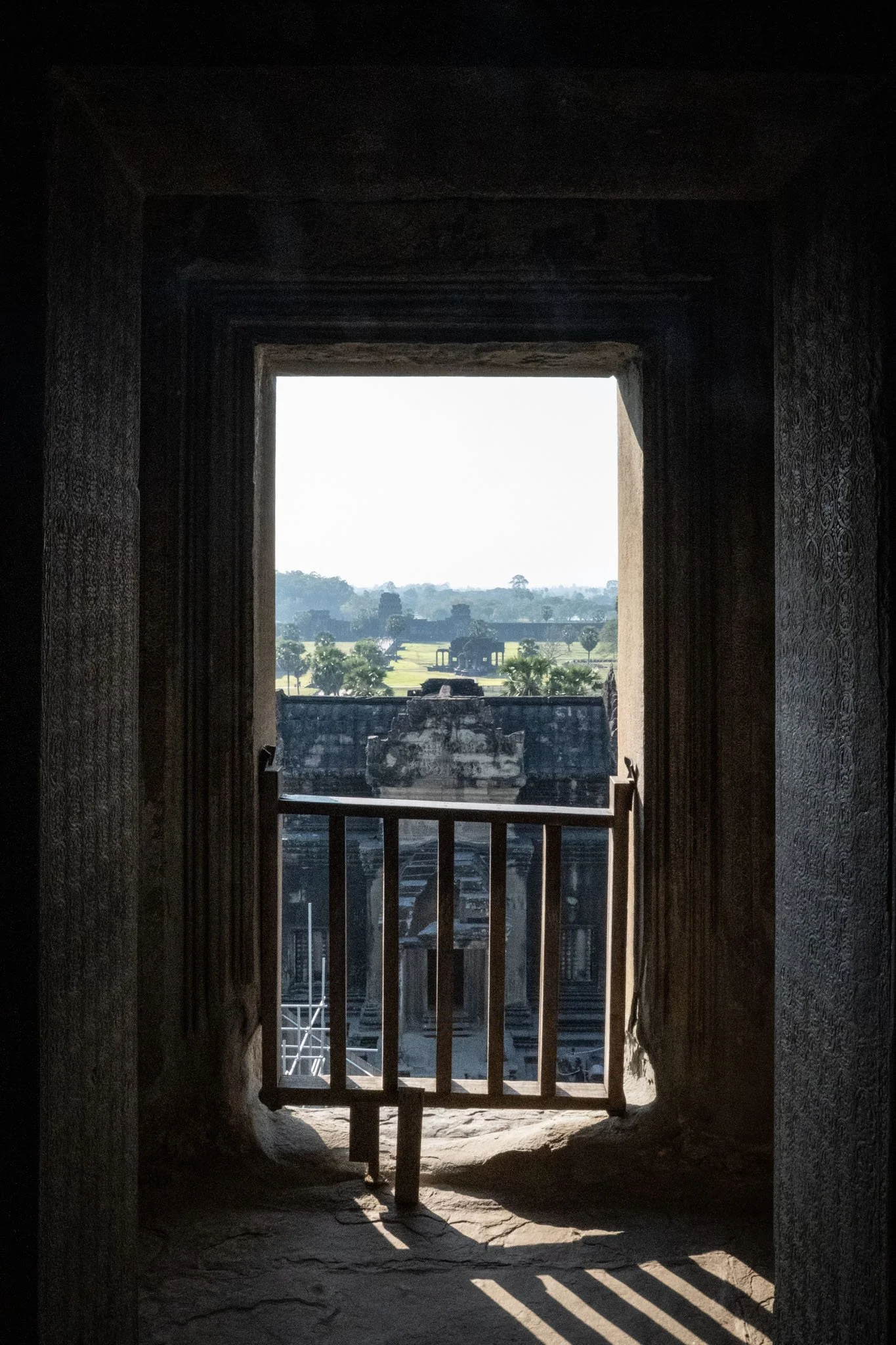

I was more or less aware of this history when I first traveled to Cambodia 24 years ago. I had read the informative but infuriating “Cambodia” by journalist Henry Kamm, whose wrapped up his book with the bleak assessment that there really was no hope for this generation of Cambodians. And I’d also read “First They Killed My Father” by the astonishingly talented Luong Ung, a heart-rending, first-hand memoir of the genocide written from the perspective of Ung, who was only five years old when the merciless “Angkar” (“Organization” in the Khmer language) destroyed her family, her home, her entire universe.

I had barged my way onto a “short term missions trip” led by an Ohio pastor I had met only a few days prior to my departure for Cambodia. I had no idea what the next three weeks would entail. I wasn’t even entirely sure why I was going on the trip – and I certainly didn’t expect it to change my life.

I flew from Columbus to Chicago to L.A. and landed in steamy Kuala Lumpur where I met up with the other team members and stayed at a spartan airport hotel before heading out on the short flight to Phnom Penh.

As the plane crossed into Vietnamese airspace, a wave of intense emotions swept over me. Not entirely surprising: I hadn’t been in – or over – Vietnam since 1998 when Kori and I adopted our son Chien from a poorly-run, under-resourced state-run orphanage in Hanoi. But as the plane crossed over into Cambodian territory, the emotions – excitement, fear, and an acute sense of gratitude – grew even stronger. Today, I’d describe it as if someone had attached a chain around my heart with a Cambodian-shaped weight on the end.

In some ways, the trip was a bust.

I had wangled my way onto the team because the pastor, Dave, needed a background singer for a band he was putting together to perform at a Christian youth conference in Sihanoukville, a shabby seaside town on the glittering Gulf of Thailand.

But I kind of hated it. Mostly because the entire thing was about us, a bunch of white guys on stage with guitars. And given the broader context of a nation which had just barely managed to climb its way out of the abyss and was struggling to cope with the predictable aftereffects of genocide – poverty, unexploded ordinance, disease, corruption, exploitation and a culture-wide case of PTSD – the last thing Cambodia needed was a bunch of white guys. On stage. With guitars.

I also kind of despised the white missionaries I met who were running the conference (and a lot of other things in the country). They dripped with contempt for any initiative that they themselves could not control, and they seemed to view their Cambodian colleagues with a nauseating blend of contempt and perpetual, paternal disappointment.

But I fell deeply, desperately and irreversibly in love with the Cambodians I met. Many were orphans. Refugees. Child soldiers. All of them had lost family members. Some of them were their family’s sole survivors: mother and father, siblings, uncles, aunts – all dead or missing.

I had expected to pity these men and women. I expected to admire them for their courage. I had not at all expected to envy them. They possessed in abundance something I had only glanced fleetingly throughout my comfortable American life:

They had HOPE.

Despite facing a hellish past and an unpredictable future, these men and women were absolutely overflowing with the confidence that God had rescued them, that he was resourcing them, and that he would use them to transform their country, to help heal physical, spiritual and emotional wounds and build a Cambodia that would not just survive, but would flourish.

Most of them were my age or younger. But they were bristling with energy and ideas. They imagined hospitals and schools and schools and churches and children’s homes and farms and factories – and they weren’t waiting on white missionaries or NGOs to give them the resources or the permission. And many of those who were bound to western organizations were straining at the reins, eager to rebuild their nation according to their own God-given blueprints.

I remember vividly sitting in the back of a church in Phnom Penh, one whose congregation included genocide survivors and genocide perpetrators. They sang enthusiastically in Khmer and at first I couldn’t place the tune. Then I got it.

“Ugh,” I thought. My cynical spirit, knotted with 30 years’ worth of annoyance at the hypocrisy and weirdness of American fundegelical subculture rolled its eyes at the recognition of the song written by Bill and Gloria Gaither, purveyors of church music I’d long dismissed as fusty.

But then I remembered the lyrics, and all of my own arrogance and cynicism evaporated (at least for a moment) as the weight of their significance struck me like a bread truck.

“Because He lives, I can face tomorrow. Because He lives, all fear is gone. Because I know He holds the future, life is worth the living, just because He lives.”

And it was then I knew I’d found it.

Jesus tells the story about a man who found a treasure hidden in a field. And when he found it, he went back and sold everything he owned to make an offer on the plot.

I’d spend the next few years trying to sell those possessions – some figurative, some literal. Dave and I teamed up to found Asia’s Hope, which started out as nothing more than legal a structure that would allow us to collect donations to send to Cambodians who started as friends, and would later develop into colleagues, partners, brothers and sisters.

Partners like Savorn – a former refugee and child soldier – who, along with his wife Sony – run Asia’s Hope in Cambodia. Both suffered greatly during what Cambodians call “the Pol Pot times.” Colleagues like the appropriately named Samnang (“Lucky”), one of our home parents who, despite having had his leg mangled by a land mine, is a far better dancer than I’ll ever be.

At first, we brought nothing more than money to the table. Today, we also bring some strategic alignment, logistical support and philosophical insights. But even as we’ve grown, we’ve maintained our rock-steady commitment to local leadership.

With an indigenous staff of around 240, we now operate 35 children’s homes, two schools, five churches, a STEM academy and six student centers in three countries. At any given time, we have about 800 orphaned and vulnerable children in our care, and fund nearly 200 university and vocational training scholarships for kids who grew up at Asia’s Hope.

And in our office in Columbus we maintain a small staff of four people who work to leverage the generous support of western churches, businesses and families for the benefit of the real leaders, the real innovators: our Asia’s Hope colleagues in Cambodia, Thailand and India.

So today as we commemorate the 50th anniversary of the start of the Cambodian holocaust, we do so not only with sorrow, but with gratitude. And with HOPE.